By Dr. Heather Mastrianno

Meet Olivia

This is a picture of Olivia in December 2021. She just turned 6 years old and started Kindergarten.

This is a picture of Olivia and her family.

Definition and Symptoms of Dystonia

This is what Olivia was experiencing:

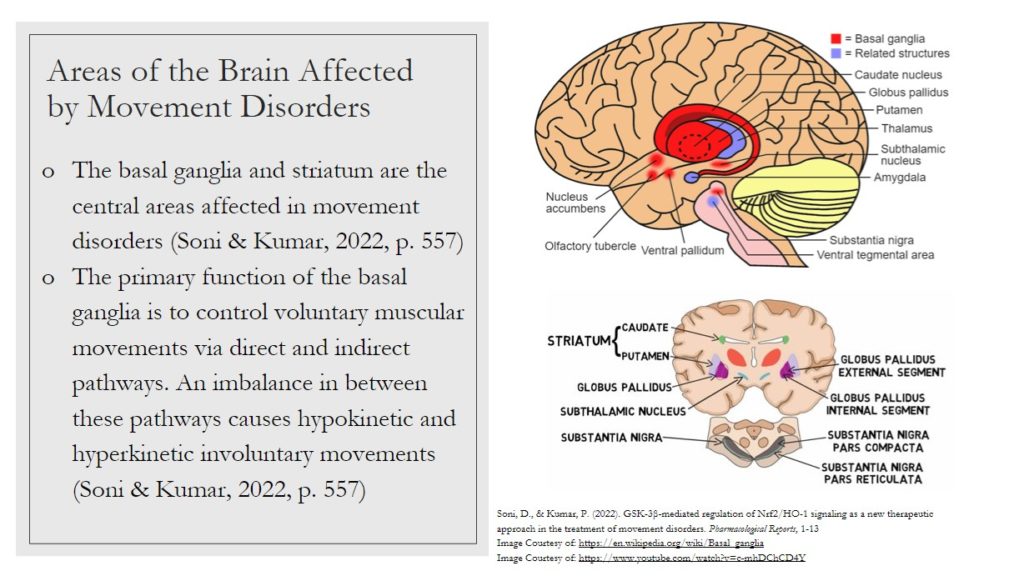

This movement disorder is characterized by the involuntary abnormal co-contraction of antagonistic muscles which sometimes cause sustained abnormal postures or twisting and repetitive movements (Abdo et al., 2010, p. 32). Dystonia involves dysfunction within the basal ganglia, cortex, cerebellum, and their inter-connections as part of the sensorimotor network (McClelland et al., 2021, p. 1).

Abdo, W. F., Van De Warrenburg, B. P., Burn, D. J., Quinn, N. P., & Bloem, B. R. (2010). The clinical approach to movement disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology, 6(1), 29-37. McClelland, V. M., Fischer, P., Foddai, E., Dall’Orso, S., Burdet, E., Brown, P., & Lin, J. P. (2021). EEG measures of sensorimotor processing and their development are abnormal in children with isolated dystonia and dystonic cerebral palsy. NeuroImage: Clinical, 30, 102569.

My first sight of Olivia’s tics:

In December 2021, Olivia began to yawn in the evenings a lot, which initially, I didn’t really think much about. One evening she got frustrated with her yawning and told me “mom I want to go to bed right now so that I can stop yawning!” I laughed, kissed her goodnight and told her that yawning was just a sign that she was tired and that she did need to go to bed, but she didn’t need to be so upset about it. At the time I thought her comments were silly and odd. Now that I look back, I realize that was the beginning of the tics.

What is a Movement Disorder?

Movement disorders refers to a group of nervous system (neurological) conditions that cause either increased movements or reduced or slow movements. These movements may be voluntary or involuntary (Mayo Clinic, n.d.).

Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022). Movement disorders. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved September 9, 2022, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-c\nditions/movement-disorders/symptoms-causes/syc-20363893

Clinical Presentation

Hypokinetic movement disorders refer to akinesia (lack of movement, hypokinesia (reduced movement), and bradykinesia (slow movement) (Western University, n.d.).

Hyperkinetic disorders are defined by jerky excessive movements that might be seen in isolation or in combination with non-jerky movements (Abdo et al., 2010, p. 31).

Movement disorders. Western University. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.uwo.ca/fhs/csd/smdl/about_smds/movement_disorders/index.html#:~:text=Hyperkinetic%20movement%20disorders%20refer%20to,slow%20movement)%2C%20and%20rigidity.

Something Might be Wrong…

Our breaking point: Monday, January 3rd, 2022. Olivia was home from school, so my husband and I had to split shifts. During the morning, I was home with her. Olivia’s tics transitioned to her full mouth opening and closing, over and over and now her head started twisting too. I tried not to cry when I saw her. I kept thinking, “How is this happening?! Where did this come from?! Is this permanent?!? Is she going to get made fun of?! What is this going to do to her self-esteem!?” I tried to call my husband to warn him it had gotten even worse, but before I could tell him anything other than “it’s not good,” he quickly became worried as he was noticing it too.

I understood. I wanted it to disappear too. I wanted to run from it, to not see it, to hope it was just a dream. The tics at this point were obvious and alarming in frequency. They were occurring about every 30 seconds to 1 minute while she was relaxing or not participating in active talking or movement. Even when she talked, when she paused, she would display the tics again.

As soon as I got to work, I got a call from my husband. He was crying. I had never heard him so distraught. He said, “Heather, it’s bad. We need to start neurofeedback now.” I checked the schedule, found an opening, and told him to bring her to the clinic in an hour. He did and so our Neurofeedback journey began.

As this was happening, I felt uniquely privileged because I had tools that most others did not: a background in and understanding of neurofeedback. I knew it would be the only answer for her because I had seen it work before. I needed to hold onto the belief and knowledge that this could help my child too. I also knew that I needed to record all of this. This was important not just for me to track my daughter’s progress, but for other mamas and daddies, daughters and sons that didn’t know about this treatment. This was bigger than me and I felt compelled to share our story with others.

Prevalence

This is the statistic category that Olivia fell into:

- 42 million people have been estimated to suffer from some form of movement disorder in the US (Michigan Medicine, n.d).

- The prevalence of tics in school-age children and adolescents can be as high as 21% (Abdo et al., 2010, p. 29).

Other statistics of Dystonia

- The overall prevalence of Parkinson’s disease is 1% in people aged 65-85 years, increasing to 4.3% above the age of 85 years (Abdo et al, 2010, p. 29).

- The overall prevalence of essential tremor is 4% in people aged over 40 years, increasing to 14% in people over 65 years of age (Abdo et al., 2010, p. 29).

Abdo, W. F., Van De Warrenburg, B. P., Burn, D. J., Quinn, N. P., & Bloem, B. R. (2010). The clinical approach to movement disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology, 6(1), 29-37. Movement disorders. Michigan Medicine. (n.d.). Retrieved September 9, 2022, from www.uofmhealth.org

My Next Steps: Google and Facebook Search

Just like any frantic parent receiving a diagnosis that was foreign to them, I pulled up my computer and started googling. Our pediatrician didn’t want to officially diagnose her with Dystonia until we did the placebo trials but the more I read and watched videos, the more I saw my daughter’s diagnosis being made clear to me. I immediately started joining Facebook groups like “Movement Disorders and Stereotypes in Children” and “Dystonia Support & Awareness.”

Again I started to see videos of kids with similar symptoms to Olivia, but I was not prepared for everything else that I saw: post after post about medications. It made me sick. I did not want my kid on a bunch of meds. Don’t get me wrong, as a psychologist I very much know the meaning and benefit of medication, but my heart broke reading everyone’s medication cocktails and suggestions. What I didn’t see was an answer or a solution that seemed right for me and my child.

Meanwhile, Olivia’s tics seemed to change and worsen. She started to yawn throughout the day and more when she was relaxing or watching TV. The yawns started to shift and looked less “natural” and more contorted.

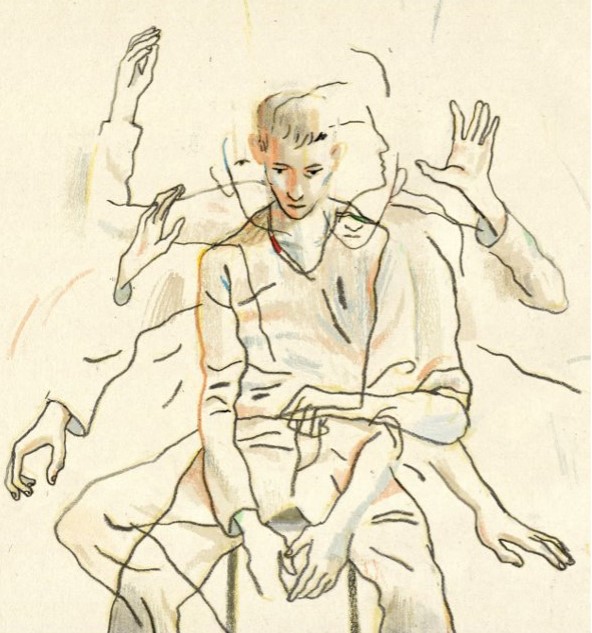

Olivia was experiencing these types of motor tics:

This is a type of hyperkinetic disorder. This movement disorder is different from myoclonus and chorea in that the patients report that their tics are preceded by rising discomfort or urge (‘sensory tic’) that is relieved by the actual movement (Abdo et al., 2010, p. 32). It is also important to note that the tics can be suppressed but suppression of tics typically comes at the expense of mounting inner tension, leading to a ‘rebound’ of tics afterward (Abdo et al., 2010, p. 32).

Abdo, W. F., Van De Warrenburg, B. P., Burn, D. J., Quinn, N. P., & Bloem, B. R. (2010). The clinical approach to movement disorders. Nature Reviews Neurology, 6(1), 29-37. Image Courtesy of: https://www.nytimes.com.

Reaching Out:

Over the next few weeks I started to reach out to people I knew. I called my mom to tell her what was happening. I was struggling emotionally with seeing my daughter like this. I worried to my mom over the phone about what the other kids at school would do, seeing her like that. I feared her getting made fun of. My mom’s advice of “starting her in yoga and making sure she has a calming environment at home” just irritated me and made me feel more helpless. I knew that wasn’t going to “work,” but I booked her an appointment with a massage therapist for a 2 hour massage anyway. It did relax her, but it didn’t change her tics.

In the back of my mind, I knew that I had something that not many other people had that gave me the hope that I needed to keep trying and going: the knowledge of and experience with neurofeedback.

After a few weeks of reading endless posts about medication, I finally posted on the Movement Disorders groups.

“Looking for anyone who has used neurofeedback for the treatment of tics!”

I got a few likes and a few people asked me what neurofeedback was. I felt so much disgust and anger after no one in these groups of 881 members and 6.9K members had seemed to have used neurofeedback for their movements disorders. I was angry that people didn’t respond to my posts, which led me to conclude that not only did people not use neurofeedback, they didn’t know about it. It also made me keenly aware that I needed to start documenting my experience, pursuing what I knew needed to be done for my kid and to give her the best shot she had for not only mitigation of symptoms, but hopefully total symptom relief.

Trying all the Things

At the beginning of neurofeedback, during the assessment phase, we not only received an EEG assessment of Olivia’s brain activity, but we were recommended to have Olivia psychologically tested. By having Olivia psychologically tested, we were able to compare what areas of the brain were under or overperforming to her mental health presentation, including her cognitive abilities.

This was not only helpful for us to know how she was cognitively and emotionally functioning, but it was a guide that was helpful for her neurofeedback technician to utilize in developing a plan for her neurofeedback training. For instance, during psychological testing, we uncovered that Olivia has ADHD.

This was not only helpful for us to know how she was cognitively and emotionally functioning, but it was a guide that was helpful for her neurofeedback technician to utilize in developing a plan for her neurofeedback training. For instance, during psychological testing, we uncovered that Olivia has ADHD.

This assisted our neurofeedback technician in choosing a protocol that not only would assist with her tics but also her concentration, which to us was a 2 for 1 and well worth the additional time.

The Otolaryngologist – Ear, Nose and Throat Doctor

Just to rule out other contributing factors, we took Olivia to the ENT to make sure there wasn’t anything in her ears, nose, or throat that may be a contributing factor to her involuntary movements. The ENT seemed surprised that I took her to see him. I explained that we had been waiting for our neurology appointment, which had to be booked very far in advance. I told him that we had started Olivia in neurofeedback as we waited and he quickly dismissed it and said, “whatever, you really need to just need to take her to the neurologist.” It was horrifying to hear a medical practitioner blow off the neurofeedback like that. I thought about how many other people may have asked him about neurofeedback and getting a response like that….it was disheartening for me, let alone another client who didn’t have a background in it.

The Pediatrician

I made a doctor’s appointment. We asked Olivia’s pediatrician about a diagnosis related to her tics and she wasn’t really sure how to answer. Our pediatrician said that we should give her a placebo, tell her that it was to treat her facial movements and if that did not improve the situation, then we should make an appointment with a neurologist. She was not clear about her diagnosis.

A neurologist?!? That was scary. It was the first time my pediatrician couldn’t help my kid.

Trying a Placebo

We gave Olivia allergy medicine during the first few weeks of December and told her it was medicine to help make the movements in her face go away. She was very excited to get the medicine, which was heart wrenching to see because I knew I was lying to her. In fact, I didn’t have an answer. I felt guilty and utterly helpless when she eagerly took this ‘medicine’ and even started asking me to take it or asking if she could take more because of how frustrating and common the tics were becoming. She started to grow increasingly frustrated by them and embarrassed when others would watch her doing them. It was clear that she couldn’t control them and it hurt me deeply to watch her deal emotionally with what was happening to her.

What is Neurofeedback?

Neurofeedback is the technique of making brain activity perceptible to the senses in order to consciously alter such activity. This is done by recording brain waves with an electroencephalogram (EEG) and presenting them visually and/or audibly to the client. An electroencephalogram (EEG) is an apparatus for detecting and recording brain waves.

- Brain activity is recorded using tools, such as sensors and an amplifier.

- After data is collected, the neurofeedback practitioner/technician interprets the data collected (the client’s brain activity, clinical questionnaires, and the client’s chief complaints/concerns) which will assist in creating a treatment plan for future sessions.

- Additional information collected includes:

- Relevant medical/mental health history

- Medications/dosages

- Previous TBIs or concussions

- Family history relevant to treatment

Olivia’s Initial Neurofeedback Session

During our initial neurofeedback session, we completed a 6 site assessment of Olivia’s brain activity, which measured the 6 main quadrants of her brain to determine how close to normative ranges they were. Following the assessment and reviewing our goals to reduce Olivia’s involuntary motor movement, our neurofeedback technician talked with us about targeting Olivia’s sensory motor cortex, which has direct involvement in bodily control of movement. She talked with us about rewarding a frequency in the brain that is 12-15HZ and called the “Sensory Motor Rhythm” (SMR). This frequency range is typically associated with calming: both emotionally and physically.

During our initial neurofeedback session, we completed a 6 site assessment of Olivia’s brain activity, which measured the 6 main quadrants of her brain to determine how close to normative ranges they were. Following the assessment and reviewing our goals to reduce Olivia’s involuntary motor movement, our neurofeedback technician talked with us about targeting Olivia’s sensory motor cortex, which has direct involvement in bodily control of movement. She talked with us about rewarding a frequency in the brain that is 12-15HZ and called the “Sensory Motor Rhythm” (SMR). This frequency range is typically associated with calming: both emotionally and physically.

Our neurofeedback technician positioned an electrode at the scalp location CZ (over the sensory motor cortex) because we wanted to view and target the activity occurring in that area of the brain.

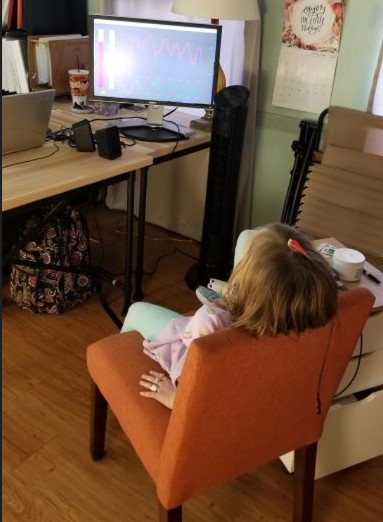

What did Olivia do During her 1st Neurofeedback Session?

During her neurofeedback session, Olivia would be watching a movie. When she was able to reward (increase) SMR activity (12-15HZ), her movie would play.

During her neurofeedback session, Olivia would be watching a movie. When she was able to reward (increase) SMR activity (12-15HZ), her movie would play.

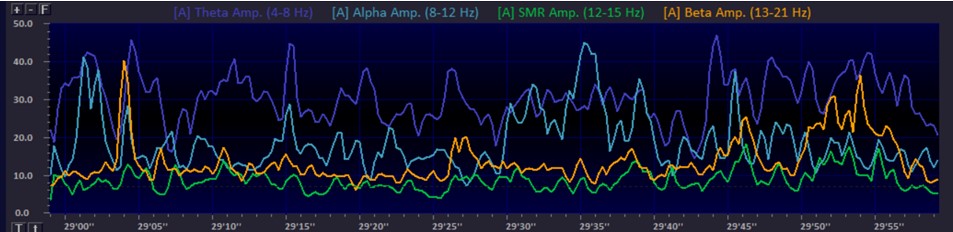

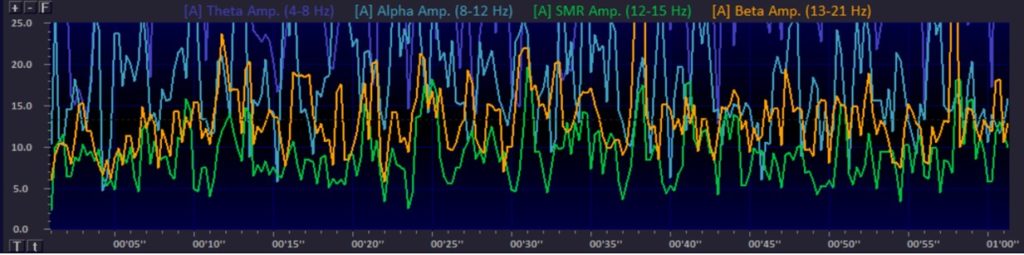

At the end of her first session, our technician reviewed Olivia’s spectral display with us. As you can see from the image below, she had some decreases in slower wave activity called Theta (4-7HZ) and some increases in a faster rhythm called Alpha (8-12 HZ), which was getting closer to the desired SMR activity (12-15HZ). Alpha activity is typically associated with calming as well. During her first session Olivia displayed some small increases in SMR. She made progress! Yay!

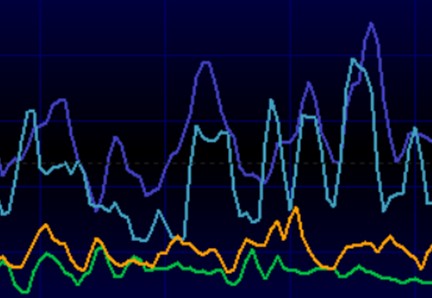

What is a Spectral Display?

![]()

This is a picture of the spectral display of Olivia’s brain activity. A spectral display is a way to view different brain waves that are occurring at a particular location in the brain.

When looking at the spectral display (above you can see that Olivia had a greater amount of Theta activity (4-8HZ) which is a slower rhythm of brain activity (the purple line). Our technician wanted Olivia to increase her SMR (12-15HZ) brain wave activity instead. SMR has been shown to be associated with calming. Research suggests that it also coincides with reductions in movement issues when it is rewarded at CZ (over the sensory motor cortex). In the picture below, the green line is Olivia’s SMR activity at the beginning of the first session.

Beginning vs. End of Neurofeedback Session

Baseline Mean of SMR activityL 6.91 (02.21.22.)

SMR Increased During Olivia’s 1st Session

n the spectral displays above, you can see how Olivia’s overall SMR activity at the beginning of her first session was about 6.91 uV. By the end of the first session, Olivia was able to increase her SMR overall to 7.95 uV! She seemed to be getting the hang of it quickly!

In Olivia’s first Neurofeedback session, she also completed biofeedback.

What is Biofeedback?

Biofeedback is a technique in which people learn to control physiological processes that are typically considered involuntary, such as heart rate, breathing, and temperature. You learn to monitor and regulate your mind and body in ways that promote mental and physical health and well-being. By receiving instant computerized feedback regarding these processes, you will learn to control, adjust, and correct inappropriate physiological processes, which will ultimately improve your health.

Biofeedback is not a passive measurement process nor a passive “treatment” process. There are various ways you can view this biological information. You can simply view the data as it changes or receive feedback via various interactive games. The process requires your active involvement in the training process in order for you to learn to control your body and improve your health.

What is EMG?

One biofeedback technique is EMG or surface electromyography. In EMG, electrodes are placed on the skin to measure the electrical activity of the muscles beneath. This gives us a snapshot of the activity and in the case of Olivia, the overactivity of her muscles.

Our biofeedback technician informed us that for most muscles we want the microvolts (the measurement for muscle activity) to be under 5 uV or even 3 uV. Olivia’s neck muscles were showing approximately 30 microvolts (uV) of activity! Likely, her hours of watching a tablet during school was not helping and her doctor suggested that this could be negatively contributing to our tic behavior.

Biofeedback for Olivia

As part of her Neurofeedback sessions, Olivia participated in EMG Biofeedback. Electrodes were placed on her neck muscles. The movie that Olivia would watch would play, when she was able to reduce the activity in her muscles.

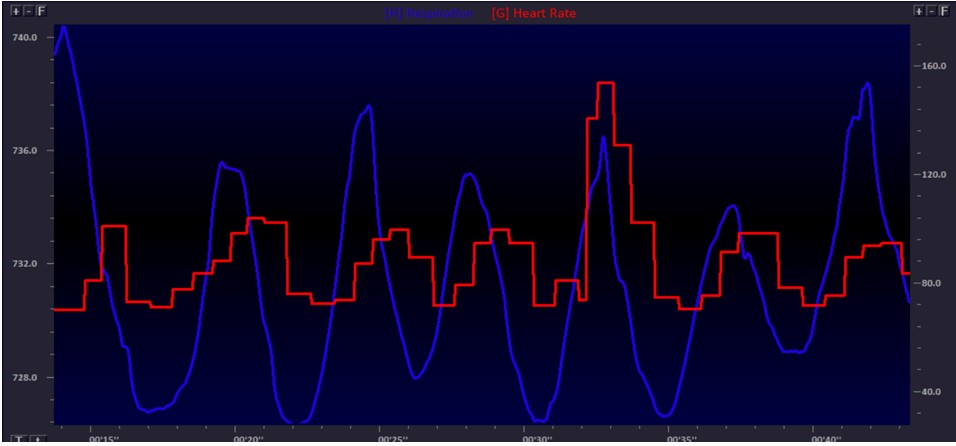

Heart Rate Variability Training (HRV Biofeedback)

In addition to EMG Biofeedback, Olivia participated in HRV biofeedback. She first learned how to reduce her breathing below 10 breaths per minute (10BPM). When clients are able to reduce their breathing below 10 BPM, they are essentially regulating their autonomic nervous system (which consists of both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems). Our biofeedback technician informed us that if Olivia was able to regulate her autonomic nervous system functioning, this could assist her in decreasing her sympathetic nervous system activity (aka the fight or flight nervous system). When overactivated this nervous system is responsible for agitated muscles, such as the muscle activity we were seeing in Olivia’s neck muscles.

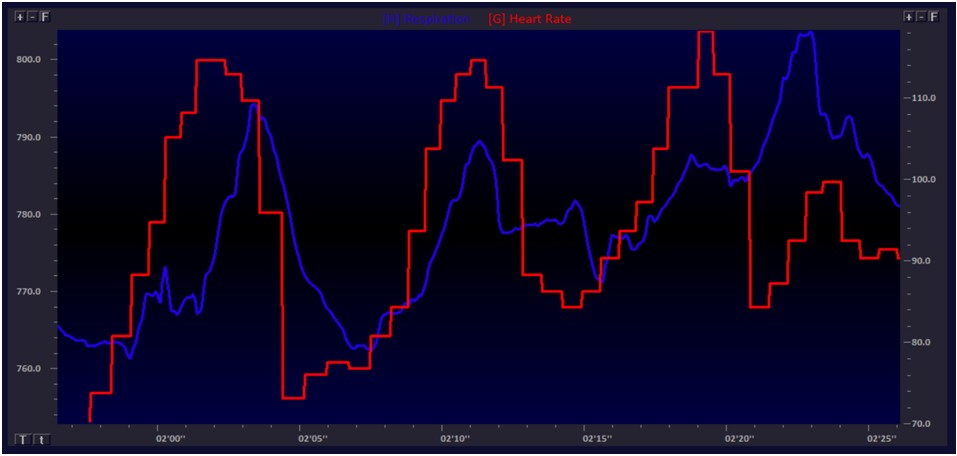

Once Olivia was able to reduce her breath rate, she was asked to try and “sync” her breath rate (the blue line below) with her heart rate (the red line below). Synchrony between your breath and heart rate mostly occurs naturally with a slowing of the breath rate to 6 BPM. This is also called the “resonant frequency of breathing” and tends to be the most optimal breathing rate to achieve autonomic nervous system balance. The practice of syncing of the breath and heart is called HRV biofeedback. Then her biofeedback technician reviewed her HRV data with us.

HRV Beginning vs End of 1st Session Data

Beginning HRV

Ending HRV

HRV Biofeedback Results

During the HRV Biofeedback portion of the session, she was able to reach 6.5 Breaths per Minute (6.5 BPM). During this portion her biofeedback technician noted that she was calm and focused. In the images above you can see toward the end of this HRV training, as her breaths slowed (the blue line), they began syncing with her heart rhythm (the red line) which signified that she was reaching a more optimal state physiologically. In this “resonant frequency of breathing” her body is likely able to recover more fully and function at its most optimal.

The Massage Therapist

After finding out that Olivia was having extreme neck tension, in addition to EMG biofeedback we scheduled her with a massage therapist. Olivia loved to get massages, which further assisted us in reducing her neck tension.

Asking Her Teacher

Meanwhile, I reached out to Olivia’s teacher. I informed her what was happening. Her teacher told me that she had noticed the movements but she reassured me that she hadn’t seen any other children making fun of her for it, which was relieving but also horrific to think about. I informed her and the school that we would be removing her from classes daily until we got a handle of her tics. Her teacher and school were very supportive of her daily neurofeedback appointments.

Typical Course of Treatment

Current treatments for movement disorders include botulinum toxin injections, Deep-brain stimulation (DBS), medications, and physical rehabilitation (Broccard et al., 2014, p. 1573). Despite the current advances in these treatments, they still present significant limitations, including undesirable effects, limited efficiency, and lack of specificity (Broccard et al., 2014, p. 1573).

Broccard, F. D., Mullen, T., Chi, Y. M., Peterson, D., Iversen, J. R., Arnold, M., … & Cauwenberghs, G. (2014). Closed-loop brain–machine–body interfaces for noninvasive rehabilitation of movement disorders. Annals of biomedical engineering, 42(8), 1573-1593.

Typical Treatment for Movement Disorders – Medication

Medications may help manage some symptoms of movement disorders depending on the disorder. Patients with Parkinson’s for instance are often prescribed medications to increase the amount of dopamine in the brain (Treatment Options, n.d.). Dopamine replacement medications are used to alleviate motor symptoms of PD. However, the other motor and non-motor symptoms are dopamine-resistant and long-exposure to dopamine replacement therapy may induce side effects such as limb proprioception, dopamine dysregulation syndrome, and motor fluctuations (Broccard et al., 2014, p. 1574).

Broccard, F. D., Mullen, T., Chi, Y. M., Peterson, D., Iversen, J. R., Arnold, M., … & Cauwenberghs, G. (2014). Closed-loop brain–machine–body interfaces for noninvasive rehabilitation of movement disorders. Annals of biomedical engineering, 42(8), 1573-1593.

Treatment options. Temple Health. (n.d.). Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://www.templehealth.org

Does Neurofeedback Work as a Treatment of Movement Disorders?

Due to the large differences in causes of different tremors, it should be understood that it is unlikely for all types of tremors to respond the same (Sanderson, 2019, p. 21). Most NFB research in the motor-movement-related field of tremors has been associated with the beta frequency band range (Sanderson, 2019, p. 21). A recent study found that by reducing theta and stimulating the motor cortex through the beta frequency, tremor amplitude could decrease (Sanderson, 2019, p. 50).

Due to the large differences in causes of different tremors, it should be understood that it is unlikely for all types of tremors to respond the same (Sanderson, 2019, p. 21). Most NFB research in the motor-movement-related field of tremors has been associated with the beta frequency band range (Sanderson, 2019, p. 21). A recent study found that by reducing theta and stimulating the motor cortex through the beta frequency, tremor amplitude could decrease (Sanderson, 2019, p. 50).

*Note: SMR activity includes part of Beta activity.

Now that traditional more invasive therapies are falling short in improving patient quality of life, new non-invasive therapeutic approaches are being researched for the neurological rehabilitation of patients suffering from movement disorders (Broccard et al., 2014, p. 1574). Neurofeedback is a neurophysiological technique that aims to teach users/patients to self-regulate targeted brain activity patterns in order to enhance cognitive abilities or reduce clinical symptoms (Jeunet et al., 2019, p. 3).

Definition courtesy of: https://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/neurofeedback Sanderson, C. (2019). Developing a neurofeedback based intervention to reduce tremor in Essential Tremor. Image Courtesy of: https://eegatlas-online.com/index.php/en/normal-variants/mu-guest Jeunet, C., Glize, B., McGonigal, A., Batail, J. M., & Micoulaud-Franchi, J. A. (2019). Using EEG-based brain computer interface and neurofeedback targeting sensorimotor rhythms to improve motor skills: Theoretical background, applications and prospects. Neurophysiologie Clinique, 49(2), 125-136. Broccard, F. D., Mullen, T., Chi, Y. M., Peterson, D., Iversen, J. R., Arnold, M., … & Cauwenberghs, G. (2014). Closed-loop brain–machine–body interfaces for noninvasive rehabilitation of movement disorders. Annals of biomedical engineering, 42(8), 1573-1593.

Using Neurofeedback to Improve Motor Skills

- Among all of the EEG targets, Sensorimotor rhythm (SMR) appears to be the most promising neurophysiological target to try to enhance motor skills. (Jeunet et al., 2019, p. 3)

- A recent study focused SMR Neurofeedback training procedures on stroke patients with the goal of reducing hypokinetic activity by training to downregulate mu Rhythm or low beta SMR activity (enhance SMR event related desynchronization). (Jeunet et al., 2019, p. 12)

- The same study focused SMR neurofeedback on ADHD patients with the goal of reducing hyperkinetic activity by training to up-regulate low beta SMR activity during attentional resting condition. (Jeunet et al., 2019,p. 12)

Jeunet, C., Glize, B., McGonigal, A., Batail, J. M., & Micoulaud-Franchi, J. A. (2019). Using EEG-based brain computer interface and neurofeedback targeting sensorimotor rhythms to improve motor skills: Theoretical background, applications and prospects. Neurophysiologie Clinique, 49(2), 125-136.

At our next session, our neurofeedback technician discussed our treatment protocol and we continued our sessions, rewarding SMR activity over the sensory motor cortex region of Olivia’s brain. Olivia didn’t seem to mind much, as she was watching a fun movie. The technician reminded us that whenever the movie would play, Olivia was demonstrating success of shifting her brain activity more toward desired ranges in the area where the sensor was placed on top of her head. We watched as the movie struggled to play initially, but by the end of the session, she was able to make it play with minimal interruption. At the end of the session, the neurofeedback technician asked her how she was able to achieve the movie playing. She said that she just tried to relax. And our sessions continued from there…

At our next session, our neurofeedback technician discussed our treatment protocol and we continued our sessions, rewarding SMR activity over the sensory motor cortex region of Olivia’s brain. Olivia didn’t seem to mind much, as she was watching a fun movie. The technician reminded us that whenever the movie would play, Olivia was demonstrating success of shifting her brain activity more toward desired ranges in the area where the sensor was placed on top of her head. We watched as the movie struggled to play initially, but by the end of the session, she was able to make it play with minimal interruption. At the end of the session, the neurofeedback technician asked her how she was able to achieve the movie playing. She said that she just tried to relax. And our sessions continued from there…

Summary of Session

Olivia had minimal tics during the session. For the Biofeedback portion of the session, Olivia completed 3 minutes of EMG training for her shoulders. For the neurofeedback portion of the session, she completed 30 minutes of encouraging SMR at Cz.

Changes Starting and then Continuing

After about 5 neurofeedback sessions my husband and I both noticed a significant reduction in her tics. By session 10, Olivia went an entire day without a tic!!! I asked my husband several times what he thought. Each time over those first few weeks of her treatments he would become extremely uncomfortable when I asked about it. He would say, “it seems good so far but I don’t want to say anything yet.” I would say, “well, you’ve seen less right?” He would respond: “I don’t want to get my hopes up.” I got that. I felt similar. Even though I knew what was happening based on my knowledge of how neurofeedback works: Olivia’s neurofeedback technician had targeted her sensory motor cortex. When Olivia was able to activate the activity their in the proper way she was rewarded with a movie playing on the screen. She was in essence exercising a new neuronal pathway in her brain, which was enhancing the functioning of this region of the brain. By doing this, she was healing her brain and the results were a reduction and eventual elimination of her tics. I knew this, but explaining it to my husband felt more like a theory. It was the results he wanted to see and the sustained results at that.

Everyday, initially, both him and I bit our lips with anticipation of seeing a tic. If we saw one we would immediately message the other about it. Over the weeks, we began to let go of the anticipation as we saw less and less.

The Neurologist Appointment (After 10 neurofeedback sessions)

It finally happened. My husband took Olivia to this appointment and I could not wait to hear how it went. My husband informed me that the neurologist appointment was “short” and “unhelpful.” The neurologist had told him that there’s good news and bad news. The bad news is that they don’t know why the tics came and went, but the good news is that they were no longer present so we could leave his office. I could not believe that not only did he not feel like the tics needed further investigation, but he completely dismissed that the absolute only thing that we did other than spend money on all of these medical professionals to give their 2 cents, was neurofeedback! And it kills me to this day that the neurologist kind of put up his hands and was like, “well, maybe it worked, but really can’t tell you because the tics are gone, so…you can go home now.”

My Experience in Video Form

https://youtube.com/watch?v=NAvlep_uiqk%3Ffeature%3Doembed

A Few Months Later

After a while, we kind of forgot about the tics on a daily basis. My husband and I forgot to be anxious about them and we got used to her not having them. When I think back to these initial days and months the fear re-emerges that they may return when she gets overly stressed or when her brain matures and prunes itself during puberty. For now, I am forever grateful for neurofeedback.

Olivia’s Treatment Continued…

Olivia began to display a few tics in the evenings during her first week of school in 2022. I wasn’t surprised because I knew that stressful times (and the first week of school is stressful) can exacerbate symptoms or cause them to re-emerge. My husband started mentioning once or twice over the months that he noticed a tic or two. Although it freaked me out, I tried to just “keep an eye on it.” I knew that 51 sessions wasn’t an “ideal” amount and I wanted her to get at least 70 in, but I tried to put it out of my head and just “wait and see.” In mid-November of 2022, I started seeing them a little more and asked her about it. She said, “Mom it’s fine, I like doing them.” I asked if she would go to neurofeedback again and she said “yes.” Although they weren’t daily or even every week, when I did see them, they were a bit more elaborate than just one and I didn’t want to wait any longer for things to worsen. During her Thanksgiving week break, I took her in again to neurofeedback.

What is a “Booster Session?”

Many times clients will ask me: “How many Neurofeedback sessions will I need?” That is a difficult question to answer. Ideally, I recommend clients to have anywhere from 50-70 sessions of neurofeedback if they want to see optimal results. I warn clients not to stop neurofeedback once their symptoms subside if it is only about 10-20 sessions in. It takes the brain time to solidify new neuronal networks, so I have seen some clients have re-emerging symptoms (although typically to a lesser extent) when they cease sessions too soon.

I also tell clients that they can do “booster sessions” like I did for Olivia. At times when the brain may be under stress (such as when Olivia started her next year of school) or when the brain is rapidly changing (such as during puberty) it is not uncommon to see an increase of symptoms. A return to neurofeedback for a shorter duration for situations like this can be helpful.

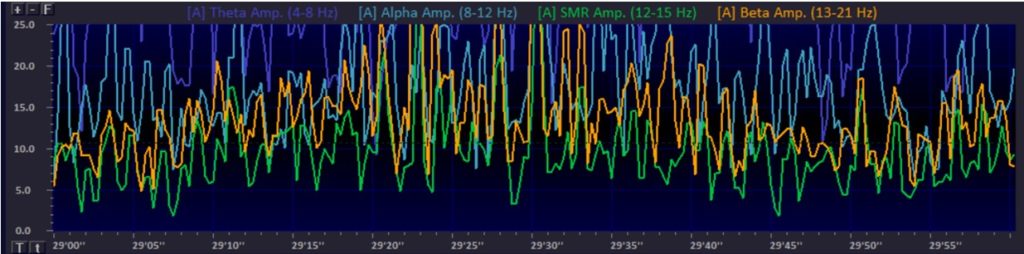

Baseline Mean of SMR activity (at the beginning of the session): 7.44 (11.23.22)

Baseline Mean of SMR activity (at the beginning of the session): 7.44 (11.23.22)

Summary of Session

We used Thanksgiving break of 2022 as an opportunity to have Olivia return for three biofeedback and neurofeedback (combined) sessions. After those sessions we did not see tics, so we decided to pause treatment again.